The Blood Type Diet, popularized by naturopathic physician Dr. Peter D'Adamo in his 1996 book "Eat Right 4 Your Type," has sparked both curiosity and controversy in the health and wellness community. The premise is simple yet provocative: your blood type—whether A, B, AB, or O—should dictate the foods you eat for optimal health. But as the diet gained traction, so did the debate over its scientific validity. Is the Blood Type Diet a groundbreaking approach to personalized nutrition, or is it merely a pseudoscientific trend masquerading as fact?

Proponents of the Blood Type Diet argue that it offers a tailored approach to eating, one that aligns with the evolutionary history of each blood type. According to D'Adamo, type O, the oldest blood type, thrives on a high-protein, meat-heavy diet reminiscent of early hunter-gatherers. Type A, which emerged with agrarian societies, is said to benefit from a plant-based diet. Type B, linked to nomadic tribes, supposedly does best with dairy and a varied diet, while type AB, the rarest and most modern, is advised to follow a mix of A and B recommendations. The theory hinges on the idea that lectins—proteins found in foods—interact differently with each blood type, potentially causing agglutination (clumping of blood cells) or other adverse effects if mismatched.

Despite its intuitive appeal, the Blood Type Diet has faced significant scrutiny from the scientific community. Critics point to the lack of robust, peer-reviewed studies supporting its claims. A 2013 review published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition examined the existing literature and found no credible evidence linking blood type to dietary needs. The researchers concluded that while the diet might encourage healthier eating habits—such as reducing processed foods—its blood-type-specific recommendations were unfounded. Similarly, a 2014 study in PLOS ONE tested the diet’s predictions in over 1,400 participants and found no correlation between blood type and the purported benefits of the prescribed diets.

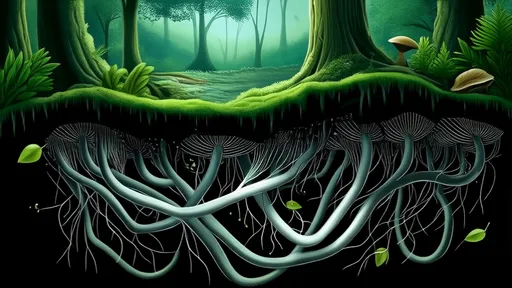

One of the most glaring issues with the Blood Type Diet is its oversimplification of human biology. Blood types are determined by antigens on the surface of red blood cells, but these antigens are just one small piece of a vastly complex genetic and metabolic puzzle. Nutrition science has increasingly emphasized the importance of individualized diets, but these are influenced by a myriad of factors, including gut microbiota, metabolic rate, and lifestyle—not just blood type. The diet’s reliance on lectins as a primary mechanism also lacks scientific backing. While some lectins can be harmful in large quantities (e.g., raw kidney beans), most are destroyed during cooking and digestion, rendering their purported blood-type-specific effects negligible.

Another point of contention is the diet’s anecdotal success stories. Many followers report improved energy, weight loss, and better digestion, which proponents cite as validation. However, these outcomes are likely due to the diet’s general emphasis on whole, unprocessed foods rather than its blood-type-specific rules. For instance, a type O individual who switches from a standard American diet to a lean, protein-rich plan may feel better—but not because of their blood type. The placebo effect and the Hawthorne effect (where people modify behavior in response to being observed) could also play a role in these subjective improvements.

The commercialization of the Blood Type Diet has further muddied the waters. D'Adamo’s empire includes books, supplements, and even blood-type-specific food products, raising questions about conflicts of interest. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with monetizing health advice, the lack of transparent, reproducible science behind the diet’s core claims is problematic. This has led some experts to classify it as pseudoscience—a system of beliefs that mimics scientific language but fails to meet rigorous methodological standards.

So where does this leave the average person seeking dietary guidance? The Blood Type Diet’s enduring popularity suggests that it taps into a deeper desire for personalized nutrition—a field that is rapidly evolving with advances in genomics and microbiome research. However, until robust evidence emerges to support its claims, it’s best approached with skepticism. For those intrigued by the idea, there’s little harm in adopting its general recommendations (e.g., eating more vegetables, reducing processed foods), but attributing these choices to blood type is more myth than science.

In the end, the Blood Type Diet serves as a fascinating case study in the intersection of science, culture, and commerce. It highlights the public’s appetite for simple, actionable health advice—even when the science behind it is shaky. As research into personalized nutrition continues, perhaps future studies will uncover more meaningful connections between blood type and diet. For now, though, the Blood Type Diet remains more alchemy than evidence-based medicine.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025