The ocean depths hold one of nature's most remarkable recycling systems—a process so efficient that a single event can sustain an ecosystem for decades. When a great whale dies and its massive body sinks to the seafloor, it triggers a chain of ecological events known as a "whale fall." This phenomenon transforms death into life, creating a temporary oasis in the deep sea's barren landscape.

A Feast in the Abyss

The journey begins when the whale's carcass reaches the seafloor, typically at depths exceeding 1,000 meters. In the darkness where food is scarce, the arrival of a whale corpse—weighing up to 160 tons—represents an unprecedented windfall. Scavengers arrive within hours, drawn by chemical cues in the water. Hagfish, sleeper sharks, and amphipods swarm the carcass, tearing into the soft tissue in a frenzy that can last up to two years.

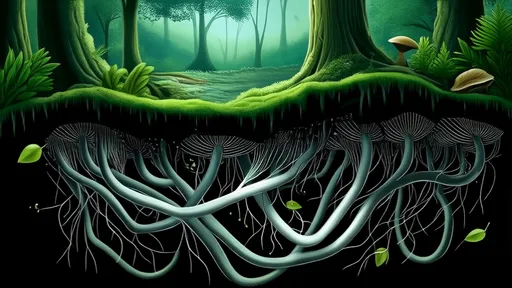

As the initial scavengers strip the flesh, the whale fall enters its second phase. Bone-eating worms (Osedax), along with crustaceans and mollusks, colonize the skeleton. These specialized organisms possess unique adaptations—Osedax worms, for instance, harbor symbiotic bacteria that digest bone collagen and lipids. The skeleton itself becomes a reef-like structure, hosting diverse communities for years.

The Microbial Revolution

What makes whale falls truly remarkable is their final act. After larger organisms have taken their share, anaerobic bacteria slowly break down the remaining lipids in the bones. This process can last decades, releasing sulfides that sustain chemosynthetic organisms—similar to those found at hydrothermal vents. A single whale skeleton might support these microbial communities for 50 to 100 years.

Scientists have discovered that certain species found at whale falls exist nowhere else. The bone-eating worm Osedax frankpressi was first identified on a whale carcass in 2002. Other organisms, like the zombie worm (Osedax mucofloris), were entirely unknown before researchers began studying these deep-sea banquets.

Ecological Significance

Before commercial whaling decimated populations, whale falls were likely common events. Researchers estimate that pre-whaling populations would have produced a whale fall every 5-16 km along migration routes. Today, with whale numbers at a fraction of their historical abundance, these events are rarer—making each discovery invaluable for science.

The loss of whale falls may have disrupted deep-sea ecosystems more than we realize. These carcasses serve as stepping stones, allowing species to disperse across the seafloor. Some scientists theorize that whale falls helped chemosynthetic organisms colonize new areas after mass extinctions.

Modern Discoveries

Advanced technology has revolutionized whale fall research. Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) now allow scientists to study these events in real time. In 2019, researchers monitoring a whale fall off California's coast observed a previously unknown behavior—octopuses stealing food from hagfish, demonstrating how these events create complex interactions.

Perhaps most astonishing is how whale falls challenge our understanding of energy flow in the ocean. A single carcass delivers approximately 2,000 times the normal organic input to the deep seafloor. This sudden nutrient pulse creates a localized ecosystem that evolves through distinct stages, supporting hundreds of species over its lifetime.

Conservation Implications

The decline of great whales represents more than the loss of majestic creatures—it's the disruption of an ancient nutrient cycle. Whales transport nutrients vertically through the water column, a process marine biologists call the "whale pump." Their carcasses complete this cycle by returning those nutrients to the depths.

Current whale conservation efforts rarely consider their postmortem ecological role. Protecting whale populations ensures the continuation of whale falls—a critical habitat for deep-sea biodiversity. As climate change alters ocean ecosystems, maintaining these natural processes becomes increasingly important.

The story of a whale's afterlife reminds us that in nature, death is never an end—it's a transformation. From a solitary giant's demise springs forth an entire community, sustaining life in the deep ocean's darkness for generations. Whale falls stand as testament to the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems, where even in death, the largest creatures continue to give life.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025