The Hidden Puppeteers: How Your Gut Bacteria Influence Your Mood

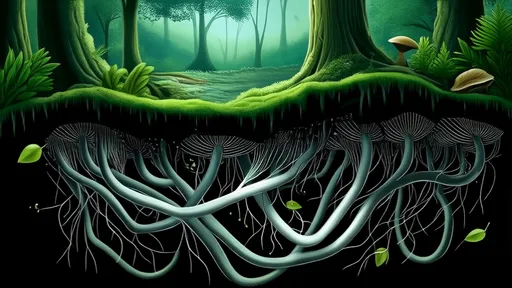

For centuries, the gut was considered a simple digestive organ, quietly processing food and expelling waste. But recent scientific discoveries have revealed a far more complex reality—one where trillions of microbes in our intestines may be pulling the strings of our emotions, decisions, and even personalities. This invisible ecosystem, known as the gut microbiome, doesn’t just break down meals; it communicates with the brain in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The idea that gut bacteria could influence mental health might sound like science fiction, but the evidence is mounting. Researchers have found that people with depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders often have distinct imbalances in their gut microbiomes. Experiments with mice show that transplanting gut bacteria from anxious rodents into calm ones can transfer the anxiety—suggesting these microbes aren’t just passive residents but active participants in shaping behavior.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Two-Way Superhighway

Communication between the gut and the brain happens through what scientists call the gut-brain axis. This isn’t just a metaphorical connection; it’s a physical network of nerves, hormones, and immune signals. The vagus nerve, a long cranial nerve stretching from the brainstem to the abdomen, acts like a high-speed cable, transmitting messages in both directions. But bacteria don’t need to send telegrams through the nervous system—they produce chemicals that directly affect brain function.

Serotonin, often called the "happy chemical," is a prime example. About 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, not the brain. Certain strains of bacteria stimulate intestinal cells to release this neurotransmitter, which then influences mood, sleep, and even appetite. Other microbes generate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a compound that helps calm the nervous system. Without the right microbial partners, these critical chemicals can fall out of balance.

Diet, Microbes, and Emotional Well-Being

What we eat doesn’t just feed us—it feeds our microbial inhabitants, and their preferences shape our cravings. Studies suggest that people who consume diets high in fermented foods (like yogurt, kimchi, and sauerkraut) tend to have lower levels of social anxiety. These foods are rich in probiotics, live bacteria that can colonize the gut and potentially crowd out harmful species. On the flip side, diets heavy in processed sugars and artificial additives may promote the growth of microbes linked to inflammation and low mood.

The relationship between food and mood isn’t just about nutrients. When certain bacteria break down fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which reduce intestinal inflammation and may protect against depression. Early clinical trials are testing whether targeted probiotic supplements could one day serve as adjunct treatments for mental health conditions. While we’re not yet at the point where psychiatrists prescribe yogurt instead of Prozac, the potential is tantalizing.

Stress and the Microbial Meltdown

Chronic stress doesn’t just fray nerves—it disrupts the delicate balance of the gut microbiome. Cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, can alter gut permeability (leading to "leaky gut") and shift bacterial populations toward more inflammatory species. This creates a vicious cycle: stress changes the microbiome, the altered microbiome exacerbates stress sensitivity, and the brain becomes trapped in a feedback loop of anxiety.

Animal studies demonstrate this clearly. Mice subjected to repeated stress show depleted levels of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus, and restoring these populations can normalize their behavior. In humans, interventions like mindfulness meditation—which reduces stress—have been shown to improve gut microbial diversity. It seems that tending to our inner ecosystem might be as important for mental health as therapy or medication.

The Future of Psychobiotics

The emerging field of psychobiotics explores how we might harness microbes to improve mental health. While current probiotics on supermarket shelves aren’t specifically designed for this purpose, scientists are working to identify exact bacterial strains that could help with conditions ranging from PTSD to autism spectrum disorders. Some researchers envision a future where mental health treatments include personalized microbiome analysis and tailored bacterial cocktails.

This isn’t to say that gut bacteria are the sole architects of our emotional lives. Genetics, environment, and life experiences all play monumental roles. But acknowledging the microbiome’s influence opens new avenues for understanding—and potentially treating—the mysteries of the human mind. The next time you feel a gut instinct or get butterflies in your stomach, remember: those sensations might not just be in your head. They could be conversations with the trillions of tiny organisms that call your body home.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025